Censorship on Instagram: “The power of the crowd threatens freedom of expression”

We can speak of censorship as soon as the holder of a power, whether state, religious or editorial, intentionally chooses to limit freedom of expression, for political, ideological, religious reasons, for security or military motivations, or even, and this is partly the case on social media, for economic reasons. Instagram is a social networking and photo-sharing application launched in 2010 and acquired in 2012 by Facebook for a trillion dollars. It is a platform that allows content to be publicly disseminated, but also a private company that can impose its own content policy. Facebook (and Instagram) is very clear about this, if you take the time (and pain) to read the terms of use. Zuckerberg’s company reserves the right to do pretty much what it wants with the posts made on its platforms.

However, Facebook has been under pressure since the 2016 elections in the United States and in a very tense context since. The company has already announced that it will pay a great attention to track down and remove content deemed offensive or “hateful” (which leaves a large space for subjectivity and interpretation) and it is doing so. However, moderation on these networks, which bring together billions of users, can only be largely automated and entrusted to algorithms that react to certain occurrences and reports. All it takes is a repeated number of reports for the account to be deleted. It is not so much censorship, in the classical sense of the word, as a form of ochlocracy (from “okhlos”, “the crowd” and “kratos”, “the power”, in ancient Greek, the term is coined in 1584 by English scholar John Stockwood), automated thanks to algorithms that reacted after a number of reports from disgruntled users.

We can then ask ourselves if all forms of sensibilities can coexist on the Internet and especially on social networks.

Cohabiting, maybe, getting along, not really. Social networks are a fantastic amplifier at the global level for an opinion fragmented into a multiplicity of contradictory opinions, which are expressed in a chaotic and often offensive way. Varity of opinions, even if it manages to exist on social networks, very often gives way to public lynching. The very principle of the “like”, at the core of Facebook and Instagram philosophy (“I like” or “I don’t like”) puts an end to the possibility of dialogue from the outset and establishes emotions and impulsiveness as the only judges. And even if Instagram, for example, tries to reduce the visibility of the “like”, the fact remains that given the massive attendance of these networks, a publication as soon as it is deemed shocking and attracts attention in a negative way, will generate a flood of comments, even insults, which quickly discourages any inclination to explain and defend one’s position in a reasoned way (unless one only has that to do with one’s days and even then the days would seem a little too short to do it).

“There is more to interpreting interpretations than to interpreting things, and more books on books than on any other subject; we are only interglossing ourselves”, wrote Michel de Montaigne in the Essays four hundred years ago. But in the same way that the industrial revolution replaced craftsmanship with mass production, social networks have shifted the “interglossage” from craftsmanship to mass production. In this context, Charlie Hebdo journalists are confronted with a media universe in which the rules of the game have changed quite brutally. When, in 1970, Charlie published his famous cover “Tragic Ball in Colombey”, the roles were somehow quite clear: the satirical newspaper provoked the state, the state reacted by censoring, which was ultimately quite gratifying for the satirical newspaper whose distribution, through the written press, remained altogether quite limited. Today, when Charlie-Hebdo remains in its niche — noisy provocation and the all-out affirmation of freedom of expression — it is not the State that the newspaper finds itself confronting when two journalists repost the cartoons on social media, but to a million-headed hydra that is opinion. Suddenly, the provocation, which in 1970 caused a stir in a still restricted political and media circle but affected public opinion in a limited way, immediately became universal. It is at the center of struggles of opinions, confrontations, tensions multiplied by the media strike force of a social network. If you add to this the rise of religious radicalism, communitarianism and Islamism which does not only spread hate speech but takes action, provocation can kill, even today as in 2015. The leaders of the companies that manage the social networks are aware of the extreme radicalization of opinions. In response, Facebook, Instagram, or even Twitter will therefore delete the content and largely rely on AI to do this work.

Content management depends on an internal sauce entrusted to Artificial Intelligence, whose intelligence is indeed quite artificial in the face of notions as humanly subtle and complex as humor, satire, derision or provocation. This is, amongst others, an essential limitation of AI today. Specialists in AI and in what is called Automatic Language Processing are well aware of the difference between the symbolic approach in the design of an artificial learning algorithm, which consists of attempting to program in upstream this algorithm to allow it to understand all the subtleties of the language, and the digital approach which consists in designing an algorithm building its own rules by digitizing as much data, knowledge and examples as possible. The first approach, which has been the subject of work by computer scientists or linguists since the 1950s, has not yielded any convincing results since no “learning software” is currently capable of understanding, integrating and anticipating all the subtleties of a spoken or written language.

The second, which could also be called “quantitative”, has been on the rise since the 1980s and still found a second wind at the turn of the 2010s with the explosion of online data (conversations, profiles, etc. ) generated by social networks. Current chatbots or moderation algorithms rely on this approach and the least we can say is that it does not allow a very subtle or truly transparent treatment of content that can be arbitrarily deleted. This trend is aggravated, as expressed earlier, by the dictatorship of reporting which leads to an almost automatic deletion of the incriminated content from a reduced number of reports. What I would therefore call “algocracy”, the “power of algorithms”, puts itself at the service of ochlocracy, “the power of the crowd”, to decide what should or should not be published. It is not very encouraging for us if we recall that, for authors like Polybius or Cicero, the power of the crowd represents the worst of regimes, the stage of supreme degeneration of democracy.

Who of the user or the platform is responsible for the content that ends up on the internet?

Both the users and the platform are responsible for the content, hence, in the current context, the extreme mistrust of social media platforms like Instagram, which establish as well as submit to the dictatorship of reporting. Given the power of these platforms, the formation of opinion in the United States and Europe has become largely dependent on them. But in Europe it is also a bit of our fault. Faced with the power of the GAFAMs, Europe remains in a defensive position and relies on a legislative offensive (GDPR, GAFA tax, etc.) to fight against the giants who make and break public opinion. But we will continue to be subject to the rule of these large social networks as long as their monopoly position has not been shaken up. In this sense, the call to build real digital sovereignty — which I signed — launched by the French company Mailo, seems to me a good initiative, unfortunately the damage began to be done when the administration of Valéry Giscard d’Estaing had taken the decision in 1978 to cut funding for the Cyclades project, led by engineer Louis Pouzin since 1972. That day, France missed the internet boat to choose Minitel and even if the most optimistic are ecstatic today that our country is one of the most connected on the planet, France and Europe have never caught up in terms of consumer digital tools. We pay the price today by observing the censorship exercised by Instagram without really being able to do much but complain about it. Freedom of expression does not fit with the monopoly of the means of expression.

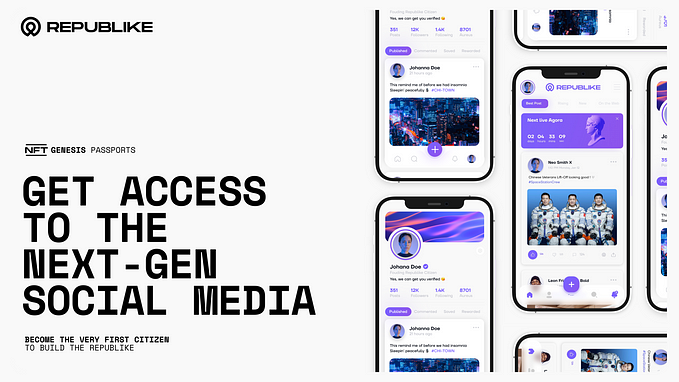

Laurent Gayard is the author of Darknet, GAFA, Bitcoin. Anonymity is a choice (2018, Slatkine&Cie) and Geopolitics of Darknet (2017, ISTE) and Board Member at Republike. From an article published in French major newspapers.